In a beautifully decorous Victorian bedroom, a middle-aged woman sits propped up in bed, a portable writing desk on her lap. Surrounding her are piles of correspondence from nurses in Britain, America and Europe: letters from Members of Parliament,reports from hospitals across England, and table and after table of statistics on mortality and morbidity rates in hospitals.

This woman is Florence Nightingale, bedridden with severe brucellosis and associated spondylitis,probably contracted during her many years working in British army and civilian field hospitals in the Ottoman Empire. Yet even as she struggled with pain, depression and limited mobility, she continued her active campaigning in public health and developing nurse training.

The traditional image of Florence is that of a willowy woman with a white bonnet, dark dress and miraculously clean pinafore, carrying a lamp,mopping fevered brows of adoring, injured soldiers as she walked her rounds at Scutari hospital in the Crimea.

The 'Lady of the Lamp' of popular mythology was likely a propaganda message promoted by the War Office to distract public opinion from the failure of the Crimean War during the 1850s.

A contemporary article from the Times described Nightingale as a 'ministering angel… her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow's face softens with gratitude at the sight of her.' (1) But the real Nightingale is a more complex figure than this popular picture suggests.

In her mid-teens she travelled widely around Europe and North Africa with various relatives. During this time, Florence formed what proved to be a lifelong friendship with the British parliamentarian Sidney Herbert. Lifelong, and pivotal, their meeting of minds would be the key that unlocked many critical doors for Florence. A few weeks before her 17th birthday, she wrote in her diary 'God called me in the morning and asked me would I do good for him alone without reputation'. However, it was not until 1850 that she found her true vocation when she visited the Lutheran religious community at Kaiserswerth-am-Rhein in Germany, where she observed pastor Theodor Fliedner and the deaconesses working for the sick and the socially deprived. She regarded the experience as a turning point in her life and returned shortly thereafter to gain formal training as a nurse.

Returning to London in 1853, she was offered the post of superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Upper Harley Street, a position she would hold for a little over a year. However, in that brief time she gained such a reputation for her clinical leadership that when reports of appalling hospital conditions came from the Crimean front, her friend Sidney Herbert (now Secretary of State for War) turned to Florence for help.

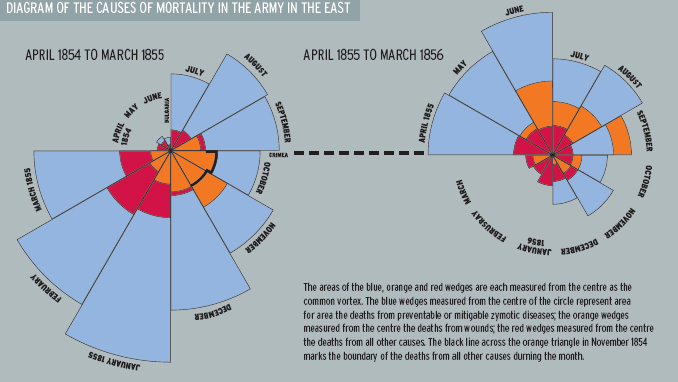

So it was that in November 1854, she arrived at Scutari hospital with a team of 38 nurses who she had personally selected and trained. Scutari (modern-day Üsküdar in Istanbul) was just 340 miles from the Crimean battlefront, across the Black Sea.When she arrived, Florence found overworked medical staff with insufficient medicines, appalling hygiene in the wards, and mass infections and high death rates. Ten times as many soldiers died from preventable infections such as cholera, dysentery and typhus, than died of their wounds.

Her diagrams, letters and pleas eventually had an impact. The War Office dispatched Isambard Kingdom Brunel to design a new, prefabricated hospital (designed to Florence's recommendations). The result was Renkioi Hospital, a civilian facility that had a death rate less than ten percent that of Scutari. Indeed, her recommendation shaped the design and practice of the other field hospitals in the war, and it is reckoned that Florence was responsible for reducing mortality rates from 42% to two percent through improvements in hygiene and aseptic practice, nutrition, ventilation and lighting.

After her return from the war, she was lauded as a hero. Yet, she continued to review her practice and that of her nurses, applying the same statistical rigour that she had used during the war. She published her mistakes and used this information to inform changes that she wanted to bring to nursing practise and hospitals in Britain. She was not afraid to show that her nurses caused deaths, and that practice needed to change, even when it showed her in a bad light.

The statistical data that Florence gathered over her time in the Crimean war, and her later gathering of similar data from hospitals across England and Europe, led her to design hospitals around what we now know as 'Nightingale Wards'. She developed a school of nursing at St Thomas' Hospital that set the standard for nursing education across the world, and established nursing as a profession with a strong evidence base. Therefore, she had great influence when it came to changes in health policy and accessing resources.

However, for all her statistical and scientific rigour and her political influence,Florence never lost sight of the need for care and compassion at the heart of nursing.

'Nursing is an art: and if it is to be made an art, it requires an exclusive devotion as hard a preparation, as any painter's or sculptor's work; for what is the having to do with dead canvas or dead marble, compared with having to do with the living body, the temple of God's spirit? It is one of the Fine Arts: I had almost said, the finest of Fine Arts.' (2)

Florence taught this to her students. But she also knew that this was only achieved through rigorous training and discipline, and constant, critical self-evaluation. She understood reflective practice long before the term came into professional usage.

Her extensive theological writings were printed in an 800 page manuscript, Suggestions for Thought,which was circulated to a few trusted friends. (3) These were not published in her lifetime, and are still largely unknown outside of scholarly fields. She was influenced by the German movement of biblical criticism, openly challenged doctrinal interpretations of Scripture and questioned conventional views of atonement. Not only is her God an 'indwelling spirit of perfection' which she strove to realise, but heaven was also to be achieved through human effort. She believed that God was to be found in the heart of every person:'Look for his thought, his feeling, his purpose; in a word, his spirit within you, without, behind you,before you. It is indeed omnipresent. Work your true work and you will find his presence in yourself'.

She did not believe in hell or judgment, rejected the idea of the incarnation of Jesus as 'an abortion of a doctrine' and saw no point in prayer for things that could be achieved by human action (why pray for the plague to pass you by when you could build better sewers and clean water systems?). She was a universalist (all will go to heaven), and fought against the expulsion of Catholics, Jews and Muslims from Anglican church hospitals. Her original team of nurses at Scutari included Catholic and Protestant lay sisters - and she had no time for any exclusive claims for the Christian faith, let alone any denomination.

Florence never joined a religious order, nor did she become an active member of any church (although in her writings she occasionally mused about starting one of her own). Her faith had a mystical edge - seeing God in everyone and everything, but she had not time for religious ritual or esoteric practices. Her mysticism was immensely practical and down to earth, worked out in compassionate care for others.In short, she had created a version of the Christian faith that suited her.

She was a scary figure in some ways - able to marshal facts and figures at moment's notice,tireless in fighting for what she believed, and not bearing fools gladly. She remains a controversial figure. Many have argued that she was never much of a nurse, more an administrator and statistician.

Others question how much of her legacy was war propaganda used to help public support for a failing war effort. However, it's hard to deny her achievements when you see her work and influence on nursing care in the 20th century. Is she a Christian hero or heretic? I would argues he was both. She was not a Christian in her beliefs about the nature of Jesus, God, humanity and atonement. In that she was definitely on the heretical end of the spectrum!

However, she did grasp that our worship of God is worked out in our care for others, and that we have a calling from God to work with him in outworking his kingdom in this world. She showed that care of the whole person was central to nursing and medicine, worthy of rigorous study and discipline. Care of the spiritual needs of our patients goes hand in hand with hygienic practice and evidence-based clinical interventions.

This woman is Florence Nightingale, bedridden with severe brucellosis and associated spondylitis,probably contracted during her many years working in British army and civilian field hospitals in the Ottoman Empire. Yet even as she struggled with pain, depression and limited mobility, she continued her active campaigning in public health and developing nurse training.

The traditional image of Florence is that of a willowy woman with a white bonnet, dark dress and miraculously clean pinafore, carrying a lamp,mopping fevered brows of adoring, injured soldiers as she walked her rounds at Scutari hospital in the Crimea.

The 'Lady of the Lamp' of popular mythology was likely a propaganda message promoted by the War Office to distract public opinion from the failure of the Crimean War during the 1850s.

A contemporary article from the Times described Nightingale as a 'ministering angel… her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow's face softens with gratitude at the sight of her.' (1) But the real Nightingale is a more complex figure than this popular picture suggests.

beginnings

Born in 1820 to a wealthy,Unitarian family in Florence,Italy, from the start Florence Nightingale had an unconventional upbringing. Schooled in classics,mathematics and the sciences by her father, she was far better educated than most of her contemporaries.Her family were not only theologically unorthodox,belonging to a church that denied the trinity and the incarnation of Jesus, but they also had apolitical heritage - her grandfather having been a parliamentarian who had campaigned against slavery with William Wilberforce.In her mid-teens she travelled widely around Europe and North Africa with various relatives. During this time, Florence formed what proved to be a lifelong friendship with the British parliamentarian Sidney Herbert. Lifelong, and pivotal, their meeting of minds would be the key that unlocked many critical doors for Florence. A few weeks before her 17th birthday, she wrote in her diary 'God called me in the morning and asked me would I do good for him alone without reputation'. However, it was not until 1850 that she found her true vocation when she visited the Lutheran religious community at Kaiserswerth-am-Rhein in Germany, where she observed pastor Theodor Fliedner and the deaconesses working for the sick and the socially deprived. She regarded the experience as a turning point in her life and returned shortly thereafter to gain formal training as a nurse.

Returning to London in 1853, she was offered the post of superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Upper Harley Street, a position she would hold for a little over a year. However, in that brief time she gained such a reputation for her clinical leadership that when reports of appalling hospital conditions came from the Crimean front, her friend Sidney Herbert (now Secretary of State for War) turned to Florence for help.

So it was that in November 1854, she arrived at Scutari hospital with a team of 38 nurses who she had personally selected and trained. Scutari (modern-day Üsküdar in Istanbul) was just 340 miles from the Crimean battlefront, across the Black Sea.When she arrived, Florence found overworked medical staff with insufficient medicines, appalling hygiene in the wards, and mass infections and high death rates. Ten times as many soldiers died from preventable infections such as cholera, dysentery and typhus, than died of their wounds.

statistician

Her diagrams, letters and pleas eventually had an impact. The War Office dispatched Isambard Kingdom Brunel to design a new, prefabricated hospital (designed to Florence's recommendations). The result was Renkioi Hospital, a civilian facility that had a death rate less than ten percent that of Scutari. Indeed, her recommendation shaped the design and practice of the other field hospitals in the war, and it is reckoned that Florence was responsible for reducing mortality rates from 42% to two percent through improvements in hygiene and aseptic practice, nutrition, ventilation and lighting.

After her return from the war, she was lauded as a hero. Yet, she continued to review her practice and that of her nurses, applying the same statistical rigour that she had used during the war. She published her mistakes and used this information to inform changes that she wanted to bring to nursing practise and hospitals in Britain. She was not afraid to show that her nurses caused deaths, and that practice needed to change, even when it showed her in a bad light.

The statistical data that Florence gathered over her time in the Crimean war, and her later gathering of similar data from hospitals across England and Europe, led her to design hospitals around what we now know as 'Nightingale Wards'. She developed a school of nursing at St Thomas' Hospital that set the standard for nursing education across the world, and established nursing as a profession with a strong evidence base. Therefore, she had great influence when it came to changes in health policy and accessing resources.

However, for all her statistical and scientific rigour and her political influence,Florence never lost sight of the need for care and compassion at the heart of nursing.

'Nursing is an art: and if it is to be made an art, it requires an exclusive devotion as hard a preparation, as any painter's or sculptor's work; for what is the having to do with dead canvas or dead marble, compared with having to do with the living body, the temple of God's spirit? It is one of the Fine Arts: I had almost said, the finest of Fine Arts.' (2)

Florence taught this to her students. But she also knew that this was only achieved through rigorous training and discipline, and constant, critical self-evaluation. She understood reflective practice long before the term came into professional usage.

mystic and theologian

What is seldom talked about is Florence's faith. Apart from espousing a call from God, what evidence do we have that she had any Christian faith? It turns out that Florence was also quite a theologian with simple mystical bent. However, her theology was far from orthodox. Though brought up a Unitarian, she had adopted the Church of England, but eschewed both the Anglo-Catholic 'high church' and the Evangelical'low church'. Instead, she was firmly at home in the liberal wing of the Anglican church.Her extensive theological writings were printed in an 800 page manuscript, Suggestions for Thought,which was circulated to a few trusted friends. (3) These were not published in her lifetime, and are still largely unknown outside of scholarly fields. She was influenced by the German movement of biblical criticism, openly challenged doctrinal interpretations of Scripture and questioned conventional views of atonement. Not only is her God an 'indwelling spirit of perfection' which she strove to realise, but heaven was also to be achieved through human effort. She believed that God was to be found in the heart of every person:'Look for his thought, his feeling, his purpose; in a word, his spirit within you, without, behind you,before you. It is indeed omnipresent. Work your true work and you will find his presence in yourself'.

She did not believe in hell or judgment, rejected the idea of the incarnation of Jesus as 'an abortion of a doctrine' and saw no point in prayer for things that could be achieved by human action (why pray for the plague to pass you by when you could build better sewers and clean water systems?). She was a universalist (all will go to heaven), and fought against the expulsion of Catholics, Jews and Muslims from Anglican church hospitals. Her original team of nurses at Scutari included Catholic and Protestant lay sisters - and she had no time for any exclusive claims for the Christian faith, let alone any denomination.

Florence never joined a religious order, nor did she become an active member of any church (although in her writings she occasionally mused about starting one of her own). Her faith had a mystical edge - seeing God in everyone and everything, but she had not time for religious ritual or esoteric practices. Her mysticism was immensely practical and down to earth, worked out in compassionate care for others.In short, she had created a version of the Christian faith that suited her.

legacy

The nursing profession as we know it today exists largely because of Florence Nightingale. She saw active compassion, evidence-based practice and scientific rigour as fundamental to good healthcare,be it nursing or medicine. She also saw the need to use evidence, convincingly communicated, as vital to achieving social and political change necessary to improve public health and healthcare provision.She was a scary figure in some ways - able to marshal facts and figures at moment's notice,tireless in fighting for what she believed, and not bearing fools gladly. She remains a controversial figure. Many have argued that she was never much of a nurse, more an administrator and statistician.

Others question how much of her legacy was war propaganda used to help public support for a failing war effort. However, it's hard to deny her achievements when you see her work and influence on nursing care in the 20th century. Is she a Christian hero or heretic? I would argues he was both. She was not a Christian in her beliefs about the nature of Jesus, God, humanity and atonement. In that she was definitely on the heretical end of the spectrum!

However, she did grasp that our worship of God is worked out in our care for others, and that we have a calling from God to work with him in outworking his kingdom in this world. She showed that care of the whole person was central to nursing and medicine, worthy of rigorous study and discipline. Care of the spiritual needs of our patients goes hand in hand with hygienic practice and evidence-based clinical interventions.

reflections

Following Nightingale's example:- Do we feel a sense of calling to our work to 'do good for God alone without reputation' ie without being noticed or praised by others?

- How willing are we to go outside of our comfort zones to follow God's calling on our lives?

- How tempting is it to re-create the Christian faith into something that fits in with the society around us, that makes us feel comfortable and leaves out the teachings that seem hard or difficult to understand?

- How willing are we to stand up for truth - even if it is inconvenient and may show us in a bad light?