If so, in what circumstances?

It shows there is still scope for doctors to share their personal beliefs within the medical consultation provided certain ground rules are followed.

The guidance also welcomes sensitive exploration of a patient’s own beliefs, as part of history-taking, provided that they are relevant to the presenting medical problem.

The new guidance has been issued with nine other sets of guidance on a range of issues alongside the revision of the GMC’s core guidance to doctors, ‘Good Medical Practice’.

All of these documents have been subject to a consultation process and I was particularly struck by how much the text has changed from the consultation draft (see below) presumably as a result of people’s feedback (See my previous articles here and here).

Like its forerunner, the new 2013 version recognises that:

‘personal beliefs and cultural practices are central in the lives of doctors and patients, and that all doctors have personal values that affect their day-to-day practice’

This helpfully give short shrift to the myth, held by some hard-line secularists, that only people who subscribe to a specific religious faith have ‘beliefs’ and ‘values’ and that atheists, by contrast, live their lives in a way that is belief and value free. The reality is very different. Everyone has a

worldview – a set of basic beliefs about the nature of reality – that profoundly affects how they think and act. This is a good starting point.

Also, like the 2008 original, the new 2013 version underlines the fact that personal beliefs need to be expressed in a way that is sensitive and appropriate.

‘You must not express your personal beliefs (including political, religious or moral beliefs) to patients in ways that exploit their vulnerability or that are likely to cause them distress.’

This is foundational. All doctors are, to some extent, in a position of power over their patients who often come to them at times of great need and crisis. I can’t see anyone wanting to disagree with this.

Absent this time, however, is any explicit statement that knowing about a patient’s beliefs can be an important in addressing their clinical problems. The following statement from the original 2008 edition has now been removed:

‘For some patients, acknowledging their beliefs or religious practices may be an important aspect of a holistic approach to their care. Discussing personal beliefs may, when approached sensitively, help you to work in partnership with patients to address their particular treatment needs. You must respect patients’ right to hold religious or other beliefs and should take those beliefs into account where they may be relevant to treatment options.’

There is however additional text this time which partially compensates for this omission by stressing the importance of spiritual factors in history-taking:

‘In assessing a patient’s conditions and taking a history, you should take account of spiritual, religious, social and cultural factors, as well as their clinical history and symptoms (see Good medical practice paragraph 15a). It may therefore be appropriate to ask a patient about their personal beliefs.’

The 2008 guidance made it clear that ‘if patients do not wish to discuss their personal beliefs with you, you must respect their wishes’ and enlarged on this at some length:

‘You should not normally discuss your personal beliefs with patients unless those beliefs are directly relevant to the patient’s care. You must not impose your beliefs on patients, or cause distress by the inappropriate or insensitive expression of religious, political or other beliefs or views. Equally, you must not put pressure on patients to discuss or justify their beliefs (or the absence of them).’

These last two sentences in this paragraph are reproduced almost verbatim in the 2013 guidance, but more care is taken to unpack the first sentence giving still, I think, scope for mutually welcomed discussion of personal beliefs:

‘During a consultation, you should keep the discussion relevant to the patient’s care and treatment. If you disclose any personal information to a patient, including talking to a patient about personal beliefs, you must be very careful not to breach the professional boundary that exists between you… You may talk about your own personal beliefs only if a patient asks you directly about them, or indicates they would welcome such a discussion. You must not impose your beliefs and values on patients, or cause distress by the inappropriate or insensitive expression of them.’

So the key question is – ‘Has the patient either raised the issue or indicated that they would welcome such a discussion?’ I don’t imagine any GP with good interpersonal skills will have much difficulty reading verbal and/or non-verbal cues to determine a clear answer to that in any given case.

Christian doctors recognise that people’s beliefs and life choices do impact health significantly and there is a

growing literature that recognises a positive correlation between Christian faith and health.

They will therefore not wish to exclude the possibility of discussing personal beliefs and values with patients provided this is welcomed, is relevant to the consultation and can be done with sensitivity, permission and respect.

They will rather see it in the context of building a relationship, practising holistic care, or as part of the normal social intercourse that may take place within any other professional/client or tradesman/customer interaction.

In other words, if you can talk to a taxi driver, hairdresser or builder about politics, morality or religion, then why should you be prevented from doing the same with your doctor if you are both up for it and have the time?

Good doctors will recognise when such discussions are appropriate and will be sensitive about professional boundaries.

Of course, the real test of the new guidelines will be the way they are interpreted and applied in practice by the GMC itself. Will we see them applied with wisdom, discretion, flexibility and tact, or will they be used as a stick to police and beat doctors with? I hope it will be the former.

Christian doctors need to be to continue to be as innocent as doves and wise as serpents: innocent as doves because we are in a position of power and patients can be needy and vulnerable, and wise as serpents because there are those who would like to stop all faith-related discussions in the medical consultation and others who will be only too willing to provide the vexatious complaints.

But this is by no means a one-way street.

Secularist doctors who reveal their own anti-religious prejudices, or who express their political or moral views in a way that exploits vulnerability, causes distress or is otherwise inappropriate need to realise that they too may be equally running the risk of censure, or worse.

Full wording of the 2008, 2012 and 2013 versions on discussing personal beliefs

9 For some patients, acknowledging their beliefs or religious practices may be an important aspect of a holistic approach to their care. Discussing personal beliefs may, when approached sensitively, help you to work in partnership with patients to address their particular treatment needs. You must respect patients’ right to hold religious or other beliefs and should take those beliefs into account where they may be relevant to treatment options. However, if patients do not wish to discuss their personal beliefs with you, you must respect their wishes.

19 You should not normally discuss your personal beliefs with patients unless those beliefs are directly relevant to the patient’s care. You must not impose your beliefs on patients, or cause distress by the inappropriate or insensitive expression of religious, political or other beliefs or views. Equally, you must not put pressure on patients to discuss or justify their beliefs (or the absence of them).

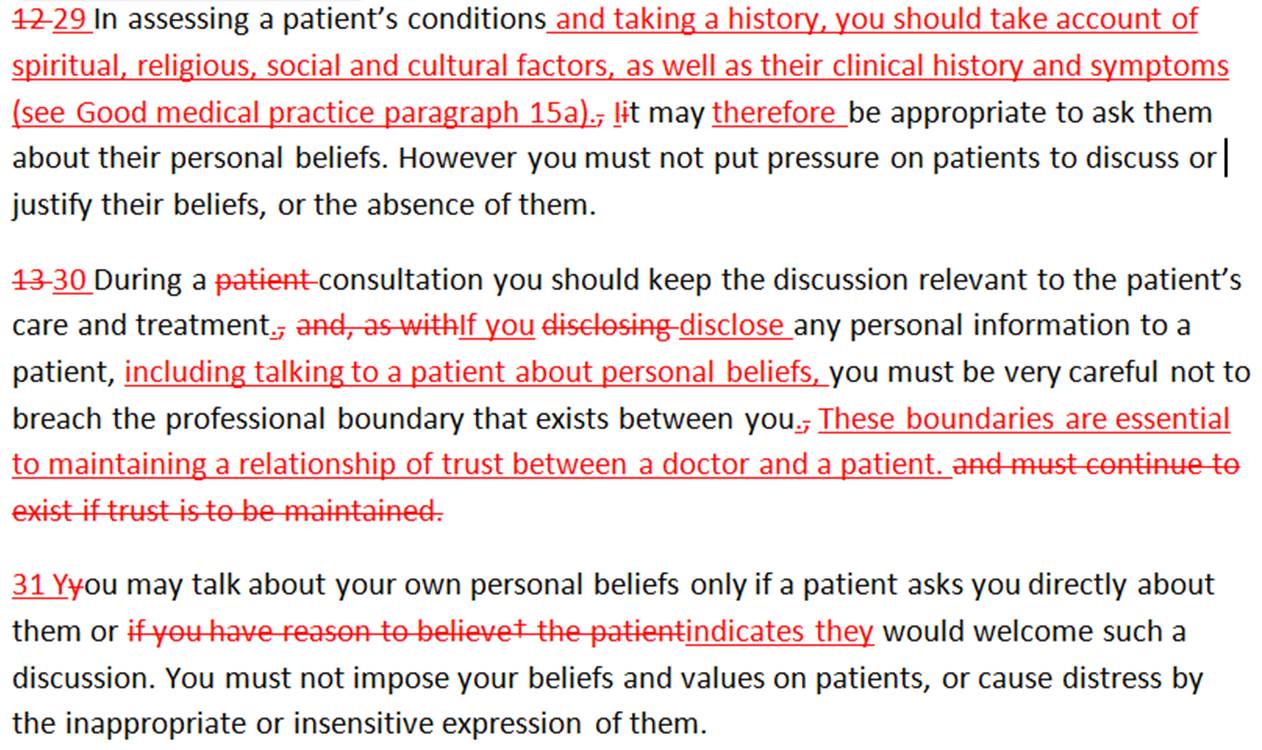

12 In assessing a patient’s conditions, it may be appropriate to ask them about their personal beliefs. However you must not put pressure on patients to discuss or justify their beliefs, or the absence of them.

13 During a patient consultation, you may talk about your own personal beliefs only if a patient asks you directly about them or if you have reason to believe† the patient would welcome such a discussion. You must not impose your beliefs and values on patients, or cause distress by the inappropriate or insensitive expression of them. You should keep the discussion relevant to the patient’s care and treatment and, as with disclosing any personal information to a patient, you must be very careful not to breach the professional boundary‡ that exists between you, and must continue to exist if trust is to be maintained.

29 In assessing a patient’s conditions and taking a history, you should take account of spiritual, religious, social and cultural factors, as well as their clinical history and symptoms (see Good medical practice paragraph 15a). It may therefore be appropriate to ask a patient about their personal beliefs. However, you must not put pressure on a patient to discuss or justify their beliefs, or the absence of them.

30 During a consultation, you should keep the discussion relevant to the patient’s care and treatment. If you disclose any personal information to a patient, including talking to a patient about personal beliefs, you must be very careful not to breach the professional boundary that exists between you. These boundaries are essential to maintaining a relationship of trust between a doctor and a patient.

31 You may talk about your own personal beliefs only if a patient asks you directly about them, or indicates they would welcome such a discussion. You must not impose your beliefs and values on patients, or cause distress by the inappropriate or insensitive expression of them.

Changes between consultation draft (2012) and final (2013) edition (tracked below)

Are doctors allowed to discuss their personal beliefs with patients or enquire about their patients’ beliefs?

Are doctors allowed to discuss their personal beliefs with patients or enquire about their patients’ beliefs?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!