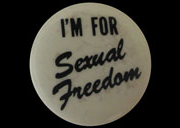

Sexual freedom and relationship breakdown cost Britain £100 billion annually

The costs of sexual freedom and relationship breakdown to the taxpayer and wider economy total some £100 billion annually; about twice as much as alcohol abuse, smoking and obesity combined.

This is the astounding conclusion of the latest ‘Cambridge Paper’, ‘Free sex: Who pays? Moral hazard and sexual ethics’, by Jubilee Centre researcher Guy Brandon.

Rather than addressing fundamental moral issues around sexual freedom, Brandon employs a utilitarian approach and attempts to quantify its financial impact. He argues that sexual freedom ‘represents an enormous moral hazard and, as a result, unsustainable and unjust public expenditure’. Furthermore, these costs are imposed on society as a whole, rather than borne solely by the individuals most directly responsible.

He first surveys the ‘changing landscape of sexual freedom’. The average age of first intercourse has fallen from 21 in the 1950s to 16 now. The divorce rate has risen from 4.4 per 1,000 in 1970 to 11.1 people per 1,000 in 2010. Forty years ago 85 per cent of first unions were marriage but now 85 per cent are cohabitations. Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) in England rose 74 per cent between 1998 and 2009 and abortions increased from 54,819 in 1969 to 189,574 in 2010.

These trends are familiar to all of us with an interest in these issues but what financial burden do they bring?

Arguing on the basis of the link between sexual freedom and the breakdown of subsequent relationships Brandon attempts to quantify the total financial burden by estimating both direct and indirect costs.

STIs are estimated to cost the NHS – and therefore the taxpayer – more than £1 billion per year. There are also longer-term costs. HIV treatment is now estimated at around £0.5 billion a year in the UK. Teenage pregnancy costs the NHS £63 million per year, and a further £29 million for infertility and other complications arising from chlamydia alone. 96 per cent of abortions are paid for by the NHS, at a cost of £118 million.

Breakdown Britain claimed that family breakdown directly costs the taxpayer £24 billion per year but the Jubilee Centre’s own analysis has shown that the figure is almost twice as high, £42 billion. Much of this comes from payments of tax credits and lone parent benefits, housing benefits, and the health, crime and educational impact of relationship breakdown.

This sum – nearly £1,400 per year for every taxpayer – is equivalent to 6 per cent of public spending for 2011.

This represents one-third of the Health Care budget, or roughly the same as the entire Defence budget or the interest on the national debt.

But £42 billion is only the immediate cost to the taxpayer of relationship breakdown. There are even larger indirect costs to the economy from absenteeism, domestic violence and educational underachievement.

Brandon estimates the annual cost to the economy of lost working hours following divorce at £20 billion, which includes both straightforward absenteeism and presenteeism (when people attend work but are distracted and unproductive due to stress).

Domestic violence costs the taxpayer £4 billion per year, and a further £3.4 billion in lost economic output. The additional ‘human and emotional costs’ are £21 billion.

Finally, there are the unquantifiable future costs of educational underachievement, worklessness, addiction and mental health problems that Breakdown Britain identified as going hand-in-hand with relationship breakdown.

Children who grow up in dysfunctional households frequently do not have the same life chances as those with more stable backgrounds. Brandon estimates, on the basis of an Australian study, that this reduces GDP by £6 billion annually.

Although the personal financial impact of sexual freedom can be high, it is often comparatively limited and the costs fall instead on the taxpayer. The UK Treasury does not make the link between the vast costs of relationship breakdown and its drivers, David Cameron’s emphasis on the family notwithstanding. Public policy barely acknowledges the existence of the problem, let alone the scale.

Brandon does not give direct references for his estimates of the financial cost of smoking, obesity and alcohol.

However, a BBC investigation in 2007 estimated the annual cost of obesity to be £2 billion to the NHS and £7 billion to the UK economy.

A 2009 Oxford University study funded by the British Heart Foundation estimated that smoking cost the NHS £5 billion annually and another Oxford study the same year estimated the cost to the NHS of alcohol-related sickness to be £3 billion.

These estimates for tobacco and alcohol costs do not include the wider indirect costs that the Cambridge paper has considered for sexual freedom and relationship breakdown.

Brandon concludes that the moral hazard that arises from our society’s uncritical endorsement of sexual freedom results in massive public costs. He argues that there are three ways of containing such an unsustainable liability, and unpacks the third preferred approach in some detail.

The current ‘Big State’ approach factors in the costs of sexual freedom, thereby actually increasing moral hazard and pushing the financial implications of individuals’ choices – totalling many tens of billions of pounds – onto the taxpayer and wider economy.

Harsh legislation to reduce sexual freedom, similar to Sharia Law, is an even less attractive option.

The third solution, found in the biblical model, is to effect a cultural change and foster greater accountability for sexual choices, strengthening extended families by increasing rootedness and giving them joint financial interests.

In this the Christian sexual ethic of faithfulness and stability has not only spiritual justification but offers a pragmatic answer to a failing culture that generally views Christian standards as hopelessly out of date.

The paper will undoubtedly stimulate debate and arouse controversy and is well worth reading.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!