Global Health – challenges for the coming year

2016 may have got a bad press in some parts of the media, but step back from the Anglophone world and the obsession with celebrity deaths and political upheavals in the West, and you get a different picture. The last year has seen many developments in global health, and in just a few short weeks we have started to see many further developments in 2017 already. What does the rest of the coming year hold in store?

2016 may have got a bad press in some parts of the media, but step back from the Anglophone world and the obsession with celebrity deaths and political upheavals in the West, and you get a different picture. The last year has seen many developments in global health, and in just a few short weeks we have started to see many further developments in 2017 already. What does the rest of the coming year hold in store?

Changing development and aid climate

For most of the last couple of decades, development funding has been led by the USA and the UK. While other nations have given larger percentages of their GNP to development than the US, it remains the largest single donor, with the UK in second place. However, recent political upheavals in both countries could see this change significantly in the near future and over the next few years.

While we do not know for certain what President Trump’s development policy will be, he has made it clear that he does not regard funding aid and development work a US priority. This could jeopardise the long-term funding of such projects as the President’s Emergency Plans for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the major funding the US gives to the Global Fund, both of which have had significant impact getting people on to treatment and resourcing effective prevention initiatives.

However, President Trump’s Executive Order that the United States will no longer fund NGOs that provide or facilitate abortion services in developing countries will have a significant (hopefully positive) impact on slowing down the drives from the global development community to liberalise laws on the termination of pregnancies in countries with stronger pro-life legislation. The precise impact will be hotly debated in the coming months. However, with a more conservative regime now heading up the Department for International Development (DFID) in the UK, US policy in this area may have more impact than it did in the first half of the noughties (when the British stepped in to fund many of the agencies de-funded for the same reasons by the Bush regime). What the impact on maternal and child health services will be is harder to gauge.

In the UK, the new government has a stronger emphasis than ever on cost effectiveness. While UK law commits the government to working toward a target of 0.7% of GDP going on overseas aid, the new Secretary of State for Development, Priti Patel, has a reputation as an antagonist to the aid community. She has already started to cut funding to projects that are seen as not providing value for money. There is also an increasing emphasis on transparency and accountability in development funding. What this will mean for global health initiatives is harder to say, but both the Global Fund and (somewhat surprisingly) the World Health Organisation get generally positive reports in a recent review of the effectiveness of recipients of UK Aid money.

Increased cooperation against established, new and emerging health threats

The last year has seen significant progress in many areas of global health and development, the results of which should start to become apparent in the coming year. The impact of both the Ebola and Zika virus outbreaks have mobilised global research on vaccines and treatments, and wider global cooperation on other preventative, public health measures. In addition, the UN General Assembly has agreed to global action on anti-microbial resistance – and while currently this is just on paper, some concrete initiatives in research and development should start to take shape in the coming year.

At the same time, some established initiatives have stalled. The Global Fund has had a successful replenishment round, but overall funding and action on HIV, TB and malaria has plateaued. There is a real danger that the gains of the last thirty years against these three big killers could be lost if funding and political support for global responses loses momentum.

The world still faces many threats from emerging viral and bacterial illnesses, especially with the increased movement of people caused by economic migration, war and environmental disasters, so such ongoing, long-term, cross-border cooperation between policy makers, scientists and clinicians will be vital.

New Technologies

New medical technologies have also emerged in 2016 that should take effect in the coming year. Large scale trials are now underway in Latin America to tackle mosquito-borne diseases with the transmission blocking–bacteria Wolbachia. This stops viral replication and transmission in infected Aedes aegypti mosquitos. Furthermore, the Wolbachia infection is transmitted down the generations of mosquitos, so a single introduction of the bacteria to an Aedes aegypti population could have long lasting benefits. This could have a marked impact on the transmission of likes of dengue, Zika and yellow fever in the long-term.

In addition, the first viable malaria vaccine candidate, RTS,S/AS01 was given the green light for pilot vaccination projects in sub-Saharan Africa by the WHO, the Global Fund and the European Medicines Agency. While talk continues of mass eradication of insect vectors for tropical diseases, vaccines and novel approaches like Wolbachia may be more promising and less ethically concerning solutions to a major health scourge.

Low cost paediatric formulations of anti-TB medications, cheap, rapid diagnostic tests for onchocerciasis (river blindness) and lymphatic filariasis, and an oral vaccine for cholera were all launched last year. And phase 2 & 3 clinical trials of low cost, highly effective hepatitis C treatments have begun. Nothing spectacular, but all could make significant inroads into major health problems facing the world’s poor.

Digital health

2017 may be the year that digital technology begins to bed in as a major force. While more people in developing countries have access to mobile telephones than clean water or electricity, it is also true that few will have access to a reliable or affordable Internet connection. Nevertheless, more data is being collected from more people than ever before, and an increasing proportion of this data is from developing nations. Biometric and demographic data collection could be used for research, public health, education, transport and housing policy planning. Telehealth is also a major growth area, making diagnostics and clinical advice available to health workers and patients in remote and under-resourced settings.

Still in its infancy, a lot of this technology is developing at an alarming rate. It also opens the doorways to cybercrime, and access to that data by some governments can be used for less positive purposes, so it is far from an unalloyed good. Nevertheless, ideas like block chain coding are being used to create anonymised economic identities for displaced people in refugee camps. This maintains privacy, protects against cybercrime, but allows refugees to buy and sell and gain some economic independence.

Conflict

War and ongoing civil conflict have been a major source of health stress in the last few years, and that looks set to continue this year. 65 million people have been forcibly displaced from their homes, five million more than in 2015. 21 million of these are officially classified as refugees. These include the spread of transmissible and parasitic infection, such as Leishmaniasis (aka ‘Aleppo Boils’) among Syrian refugees, to the health challenges faced by those living outside official camps with no access to good sanitation, potable water, nutrition or healthcare.

The refugee crisis may be the single, largest driver of global health threats in the coming years, and is certainly the biggest, single humanitarian crisis to face the world in decades.

Demography

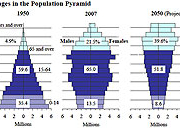

A third of all people on earth today are aged under twenty. However, in the 30 wealthiest countries that proportion falls to less than 20%. In short, the wealthy are mostly old, the poor are mostly young. Furthermore, this poorer, younger population is finding it hard to get work; only 40% are likely to get a job, leaving at least 600 million young people without employment, education or training. The net result will be more and more mass migration to find jobs and other life opportunities, more social unrest and the potential for riots, civil conflict and social breakdown.

This is further exacerbated by the imbalance of the sexes in many developing countries. Preference for male children, low birth-rates or external restrictions on family size and easy access to abortion have all led to a female ‘gendercide’ (still largely unreported). This means that there could be as many as 130 million fewer women in the world than would be expected. This is particularly a problem in Asia, and most especially in China. The bad news is that this means a generation of young men for whom marriage prospects are poor. The evidence is strong that unmarried men tend to be more likely to be a cause of crime and violence, but also are more likely to die younger and suffer worse health. Furthermore, the lack of young women in many societies increases the incidence of abductions and trafficking of young women and girls from poorer nations. The good news is that this trend seems to be diminishing, and that birth ratios are drifting back towards parity. However, it could be another couple of generations before this has any real effect on adult sex ratios.

The mass movement of populations will also significantly affect the spread of communicable disease, the incidence of physical injury and mortality (consider the number who have died trying to cross the Mediterranean in just the last two years!), and the pressure on health services in host nations.

Challenges for Christians

All these challenges and opportunities are global in their implications. For the church and Christian Faith Based Organisations involved in healthcare provision the current situation is both a threat and an opportunity. One threat is in the rising tide of persecution faced by the Christians in many parts of the world, making it harder to minister to those in need. Another threat is in the increasing opposition to the Christian positions on early life and end of life care. Drives to eliminate freedom of conscience and funding restrictions to faith based organisations who share faith or who have ethical restrictions on procedures they will provide, are making it harder in some parts of the world to act with a Christian ethic.

However, within the UN system and the wider global health community, there has been an increasing awareness of the need to work with faith communities and faith based organisations. Christians are by far the largest and one of the best organised and networked faith communities addressing global health needs, and the chance to have a real impact on areas of need by developing constructive (but not constrictive) partnerships with international agencies and governments cannot be ignored.

The Sustainable Development Goals, for all their inherent limitations, still present a great opportunity for Christians to engage constructively with the wider global community to effect real change.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!